Execution

The vast majority of those put on trial at the Old Bailey in the eighteenth century and up to the 1830s were, at least in theory, exposed to the threat of the death penalty. In practice, however, through various mechanisms including partial verdicts and pardons, many of those who were tried and convicted ultimately suffered a lesser form of punishment. For the minority of offenders who were denied such mercy, however, the consequences were fatal and shockingly cruel.

Death Sentence Respited

In a small proportion of cases the court decided to postpone or respite the passing of a death sentence on capital convicts. Such respites were common in the eighteenth century, particularly women respited for pregnancy. In 1848, the process for respiting convicts changed: judges were now empowered to invite the jury to respite sentences in cases where the law was doubtful. In these instances, the case was passed on to the twelve judges at the newly established Court for Crown Cases Reserved (superseded in 1907 by the Court of Criminal Appeal).

Most commonly, death sentences were respited for pregnancy. At the point of sentencing, women who claimed that they were pregnant could “plead their belly”. A jury of matrons (chosen from women present in the courtroom) would then examine the female convict. If they determined that the woman was pregnant (often referred to as "quick with child"), the death sentence was respited until after the baby was born. In many instances such women were ultimately pardoned from execution. From 1848, reprieves granted to pregnant capital convicts were always permanent. Such cases were becoming rare, however: after 1800 there are few recorded cases of female defendants at the Old Bailey who made a plea of pregnancy. Claims of pregnancy and the penal outcomes in such cases can be studied through the Old Bailey Proceedings and Capital Convictions at the Old Bailey 1760-1837 records included on this site.

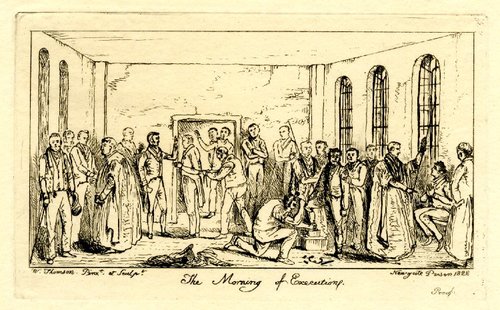

Hanging

Those capital convicts who received no such respite of their death sentence were held in the condemned hold in Newgate. There they would wait for the news of the "Recorder’s Report" and the resulting "Dead Warrant" — the list of the condemned who had been denied pardons and thus left for execution.

On the Sunday before the execution, the Ordinary of Newgate would preach a sermon to all the prisoners, with the doomed offenders at the front for all to see. The bells of St Sepulchre’s church next to Newgate would be rung at midnight on the night before the execution, and on the morning itself prayers would be read and the sacrament administered before the condemned made their journey to the gallows.

At Tyburn

Until November 1783, most Old Bailey defendants were hanged at Tyburn (where Marble Arch now stands). Convicts were drawn in a cart through the streets for the two and a half mile journey from Newgate to Tyburn. Huge crowds often lined the streets or waited for the procession at Tyburn. The convict was then given a chance to speak to the crowd and make their final preparations, before being blindfolded and haltered. The cart was then pulled away, resulting in a long and painful death by strangulation.

Outside Newgate

In 1783, in an attempt to reduce disorder the procession to Tyburn was abolished, and from December of that year the majority of Old Bailey executions were carried out on a gallows erected just outside Newgate prison. A "drop" mechanism was also introduced, in an attempt to reduce the convict’s suffering and expedite the spectacle. In many other parts of England and Wales similar changes were also made.

The executions outside prisons were however still very public occasions and were increasingly criticised for "brutalising" the crowd and failing to serve their intended purpose as a deterrent. In 1868, these concerns led to the abolition of public executions. Hangings in London were subsequently transferred to inside Newgate. The last hanging at Newgate was carried out on 6 May 1902. Thereafter, Old Bailey executions were conducted on a gallows inside Pentonville prison.

Other Locations

Whilst the vast majority of executions in London took place at Tyburn or at Newgate, other execution sites were used. Those condemned at the Admiralty Sessions held at the Old Bailey for offences committed at sea were hanged at Execution Dock in Wapping. Traitors tended to be executed at Tower Hill. In a few dozen instances, meanwhile, the offenders were taken in procession to the scene of their crime (or some other symbolic location other than Tyburn) and there executed, many of whom were hung in chains afterwards.

Burning at the Stake

Females who were capitally convicted of either treason (typically coining) or petty treason (usually the murder of a husband or master) were sentenced to be burned alive at the stake. In almost all instances, however, the offender was strangled by the hangman before the fire was lit. Burning at the stake was abolished in 1790. In cases of treason it was replaced by drawing and hanging. In cases of the murder of a husband or master, it was (until 1832) replaced by hanging with dissection.

Hung, Drawn and Quartered

Males who were capitally convicted of treason (typically involving coining or conspiracy against the Crown) were sentenced to be drawn to the place of execution on a hurdle, and there to be hanged, cut down while still alive, and then disembowelled, castrated, beheaded and quartered, with the body parts sometimes spiked on poles at public locations. In practice, such punishments were often mitigated, with those convicted of coining not sentenced to the horrors of dismemberment. In the early nineteenth century, the practice of quartering was abadoned, with offenders typically now hung until fully dead and then decapitated. The Cato Street conspirators were the last offenders to suffer this fate in England and Wales, in 1820. The punishment was not however repealed from the statute books until 1870.

Dissection and Hanging in Chains

In 1752, an Act “for better preventing the horrid crime of murder” was introduced in England and Wales. This stipulated that the bodies of convicted murderers should, after their execution by hanging, be either “dissected and anatomised” or suspended in irons on a gibbet (a high post), and that in no instance should the body be buried in consecrated ground. Moreover, it specified that such murderers should be executed on the next day but one after sentencing (unless that happened to be a Sunday), and that while awaiting their execution the offenders should be held in solitary confinement and fed on a diet of bread and water alone. The majority of those so convicted of murder at the Old Bailey were sent for dissection, rather than hanging in chains. Dissection as a punishment for murder was abolished in 1832, with hanging in chains abolished two years later in 1834. By the mid-1830s, therefore, the practice of mutilating the corpses of executed offenders had effectively ended.

The Rise and Fall of the Bloody Code

In 1688, about 50 offences carried the death penalty. By 1815 this had increased to over 200. This “bloody code” mostly targeted property offences and types of crime that were seen to be on the rise, such as shoplifting and theft by servants. Many of the statutes were narrowly defined, and few were applied in practice, so the number of executions did not rise in line with the increase in statutes. By the early nineteenth century, this messy patchwork of capital statutes was widely criticised as an ineffective and incoherent body of laws. In the 1830s most offences were made non-capital, bringing an end to the bloody code. By 1861, the death penalty had been abolished for all crimes except murder, high treason, piracy with violence and arson in the royal dockyards.

Execution Rates

Execution rates at the Old Bailey fluctuated greatly over time between the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and contrasted markedly with those in other parts of England and Wales.

The absolute number of offenders put to death in London was especially high in the 1780s in the wake of the penal crisis which followed the end of transportation to America, the Gordon Riots, and the demobilisation which followed the end of the American War. Considerable numbers were also executed in the 1820s, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, in contrast to relative lows between the 1790s and 1810s. Execution levels collapsed in the 1830s following the abolition of most offences from the death penalty.

This Old Bailey execution rate far outstripped any other court in England, Wales or the wider western world. The per-capita execution rate in London in the third quarter of the eighteenth century was, at 3.85 executions per 100,000 population, over fifty times higher than the average for the counties with the lowest rates in England and Wales, including Cornwall, Durham and Anglesey. Nor did the towns and regions of the white "settler" colonies of the British Atlantic or the major cities of Europe execute anywhere near as many criminals as were put to death by the Old Bailey. By the early nineteenth century, the disparity between execution rates in London and in other parts of England and Wales was far less extensive than it had been in the previous century. In the major industrialising and manufacturing areas of England, such as Lancashire, execution levels in fact started to overtake those of London for the first time.

Records in the Digital Panopticon

Death sentences and the resulting executions for those who were not pardoned can be studied in detail through a number of sources included in this website. The Old Bailey Proceedings provides sentences, while the pardoning process is documented in the Judges Reports on Criminals 1784-1827 and Petitions for Pardon 1797-1858. The Capital Convictions at the Old Bailey 1760-1837 records provide the outcomes for every convict sentenced to death in those years.

Further Information

- Devereaux, Simon. "England’s 'Bloody Code' in Crisis and Transition: Executions at the Old Bailey, 1760–1837." Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 24 (2013): 71–113.

- Devereaux, Simon. "The Bloodiest Code: Counting Executions and Pardons at the Old Bailey, 1730–1837." Law, Crime and History 6 (2016): 83–102.

- Gatrell, V. A. C. The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770–1868. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- King, Peter, and Richard Ward. "Rethinking the Bloody Code in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Capital Punishment at the Centre and on the Periphery." Past & Present 228 (2015): 159–205.

- McKenzie, Andrea. Tyburn’s Martyrs: Execution in England, c.1675–1775. Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

Author Credits

This page was written by Richard Ward, with additional contributions by other members of the Digital Panopticon project team.